Buildings for extreme environments

Published in Stories from Supple, 11 June 2018

Hugh Broughton is a British architect and one of the world's leading designers of buildings for extreme, isolated environments. In 2005 his practice Hugh Broughton Architects won the international competition for the design of a new British research station in Antarctica. This has led to commissions in other extreme, isolated environments as well as further commissions in polar regions. I spoke to Hugh about the polar research station he designed for the British Antarctic Survey as well as some of his projects in other inaccessible environments.

How did you become involved in the design of the British Antarctic Survey’s new Halley VI Research Station?

To a degree, it came about by chance. The British Antarctic Survey was running a competition in 2004 for designing a relocatable polar research station in the Antarctic. I went along to the launch of the competition after hearing an interview with Chris Rapley, then Director of the British Antarctic Survey, on Radio 4. When I heard Chris talking about how the winning company needed to be an expert in prefabrication and sustainability as well as have a track record of working in remote locations around the world, I thought our chances of winning were slim. At the time, we were a four-man office and the biggest building we had designed was 150 square metres for the Girl Guides in Wimbledon.

I think winning the competition was one of those collusions of good fortune that sometimes happen in life; I met up with an engineer from Faber Maunsell after the launch event and he wanted to submit an entry with us. Ultimately, we were fortunate that the British Antarctic Survey was looking for a tried and tested engineering company to work with a young architecture company that could offer challenging ideas. I had no experience whatsoever in designing polar research stations before the competition, but on the other hand neither did any other architects. The American base at the South Pole was designed by a Hawaiian architecture firm called Ferraro Choi, however other than that, architects had not really been involved in designing buildings for polar regions. Therefore, all the submitting architecture firms to the British Antarctic Survey were on a rare level playing field. The big firms all went for it, but they had no more experience than we did with this particular type of project.

What was it about your submission that made you stand out?

I think in the end it came down to two things. Firstly, we had this idea of using flexible modules that could be used for lots of different functions. Secondly, we put a lot of effort into the interior design and interior environment of the station. We did drawings of the day in the life of a scientist on the station, and tried to imagine all the different scenarios of living with that degree of isolation. The sun doesn’t rise above the horizon for 105 days of the year in the Antarctic, and often the weather can be so bad you are stuck inside for weeks at a time, so the interior space needs to allow for variety in daily life. We worked with a colour psychologist who came up with a palette of colours that would help people overcome seasonal affective disorder as well as promote different activities. For instance, in the bedroom all the duvets were peach because that is the best colour for helping you get to sleep. We also worked with Philips to develop a special light that would go above the scientists’ heads and wake them up with a false dawn of daylight simulation, another method of helping them overcome seasonal affective disorder. Smell was also considered; we had a staircase going up to the upper level of the main social module that was lined in Lebanese cedar veneer because, of all the veneers, that is the one that gives off a smell closest to the tree. It is a nice, natural, subliminal message as you are moving around. When you are trying to help people through what is an extreme living experience, it is incumbent upon you as a designer to try and think of every small way in which you can improve their lot.

What was the thinking behind the bright blue colour of the modules?

There is a scientific aspect to the choice of blue and red as the module colours, which are darker colours because if you use light colours you get intense solar reflection off the ice surface and you do not want this to bounce back off the building because it causes snow and ice to melt under the feet of the building and differential settlement. We also wanted to reflect the Antarctic environment; with ice and icebergs you get these incredible blues, so we sampled some of those blues and choose one of them to be the colour of the module. There was a combination of art and science in making the decision.

How did your experience designing a building for the Antarctic influence your designs for buildings in more urban environments?

Up until Halley VI we were working mainly on urban projects and with existing buildings. Winning the Halley project led to us becoming involved in a series of other buildings for polar environments; from no one having any experience suddenly we had more experience than anyone else, so we started getting involved in the design of polar research stations for other countries such as Spain, America, Brazil and India.

It is not always easy to perceive how the lessons we have learnt from designing buildings for the Antarctic have been applied to other jobs, but I think there was a high level of coordination needed and there was a first principle idea when we were designing for the Antarctic, particularly with things like the interior environment. Either openly or subliminally you start thinking more clearly about designing from first principles rather than coming up with a shape or a form or something like that. It is a more considered way of designing, combining engineering, operational and emotional responses.

Was it always the intention to become involved in projects in other extreme, remote regions?

I developed a personal interest in extreme, remote, natural environments through the Halley VI Antarctic Research Station design process, and it has been intentional to pursue an adventurous line of work since the completion of the project. I like that element of adventure about it, the different places it takes you to, not only in terms of sites, but the different people you work with or the research you carry out to complete these projects. There is also an element of other people wanting to find out more about the projects, so an interesting lecture circuit has developed out of it too - it has added variety, that is for sure.

The polar market is fairly limited and once you have done Britain, while the other countries might be interested in your early ideas, they are not necessarily interested in the delivery because there is a degree of national pride in these projects. Therefore, I am always casting my tentacles about to try and find other areas where our experience designing for remote environments might be appropriate.

There are interesting technical and human factor aspects to working in extreme environments. For example, I met an engineer from the European Southern Observatory, which is based in the Atacama Desert in Chile. There they have a vast array of telescopes looking out into deep space and the Milky Way and so on. They are at really high altitude and they are thinking of going even higher where they would need to support a technical team looking after the telescope for long periods at a time, when oxygen levels are depleted, the temperature is really low and there are incredibly high levels of UV exposure. I find the technical challenges that come with designing buildings for extreme environments, and the opportunity to support people doing scientific research that we are in the long term all going to benefit from, very invigorating.

Please can you talk about some of the other buildings you have designed for extreme, remote environments?

We have worked on a number of other isolated projects, including a hospital on Tristan de Cunha, the remotest inhabited island in the world, which is eight days sailing off the coast of South Africa in the Atlantic. We are also working on a building for the Ministry of Defence on St Kilda, an island in the remotest part of the British Isles, a hundred miles off the coast of Scotland. We have started working with the British Antarctic Survey again too; their new boat, the RSS Sir David Attenborough, has replaced their two old ships and it is much bigger so needs a new wharf and a number of new buildings. There are a lot of lessons learnt from our work in Antarctica in terms of logistics, prefabrication, maintenance, and interior design, that are transferable to these projects.

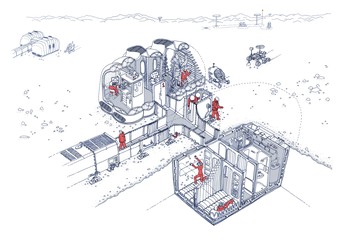

Does the prospect of designing for lunar environments interest you?

The engineering of any kind of vehicle going into space is phenomenally sophisticated and there are millions of people who know more about that than I ever will. However, where the space industry has sought our opinion is on ergonomics and the ability of people to live in extreme environments in isolation for long periods of time. In the past, when people have designed spaceships they have started with the engineering and then at the end you are left with a small amount of space for the astronaut, which is not a huge issue if you are going to the moon or a space station because it only takes a short time. But if you go on a long duration mission to Mars, depending on the trajectory, it is 9 months or 18 months, which is a long time. NASA asked our opinion on how much private space astronauts might need on a mission to Mars; they did not want engineering to dictate the space an astronaut is left with, they wanted to dictate to engineering the space an astronaut would need. Along with other experts we advocated that the minimal habitable volume of living space per astronaut on a long duration mission to Mars would have to be 20 cubic metres per astronaut.

Does working in these remote, extreme, isolated locations heighten your consideration for the environment and nature in your designs?

Sustainability and a responsibility to the environments where you are working are important. I think carefully about the impact on the environment, wildlife, and flora and fauna, to make sure the touch is as light as possible. That sense of responsibility to the environment that you ought to feel as an architect anyway, wherever you are working, is certainly heightened working in remote locations where man’s very existence is fairly delicate and tenuous.

How can scientists access fresh food and greenery when living in a polar research station?

When we did the competition entry for Halley VI we put a hydroponic salad garden as a centrepiece in the atrium of the main module. The aim was for it to produce greenery and salad three times a week so a winter crew would have access to fresh food. The mistake I made was placing it in the middle of the central module because it needs tending; when it is harvested it is like an empty greenhouse, and there are certain nutrients which are smellier than others, which is not ideal in the main living space. Sadly, it bit the dust and I blame myself for putting it in that central place, because if we put it anywhere else it might have worked. The evidence for that is the hydroponic salad garden in the main South Pole station; it is so popular that they have introduced a booking regime. People book it for half an hour slots to read their book and relax because it has very bright light, a very pleasant smell when it is in flower, and is very humid. Bright light, smell, and greenery all counteract the sensory deprivations you suffer when you live in the Antarctic, so that is why people love it so much. People also love saunas, because it is so dry in the Antarctic all the moisture gets wicked out of the air.

More news

News 30 November 2020

A new era of Australian Antarctic endeavour

The Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) has appointed Hugh Broughton Architects to join a team led by multi-disciplinary consultants WSP to masterplan the modernisation of the infrastructure at Davis research station in East Antarctica. Initial masterplanning is now complete, and masterplan concept development is ongoing.

News 26 October 2020

Building a Martian House

A full-scale house designed for future life on Mars has received planning permission in Bristol. The house is the outcome of an ongoing public art project, ‘Building a Martian House’.