A conversation with Hugh Broughton

Published in AIA Dallas Springboard, 3 April 2017

In a recent Dallas Architecture Forum speaking engagement at The Magnolia Theatre, Hugh Broughton showcased some of the practice's work for the Polar regions as well as other renovation and rehabilitation projects.

The following day, Ryan Flener of Good Fulton & Farrell Architects, had the opportunity to meet with him to discuss his ideas, practice, and thoughts on Dallas.

First of all thanks for spending some time with us. We really appreciate it. You’re from London correct?

That’s correct!

You’ve spent some time in Dallas over the past few days. How do you like it so far?

It’s absolutely fantastic, especially for an architect. It’s like a dream come true, visiting some of the buildings you have both here and in Fort Worth.

I wanted to go ahead and jump right into some of your work. We saw your lecture on Wednesday night. You speak very well about your projects and know them well. There were no papers. Do you practice this often?

I think the Antarctic project in particular has been of interest to quite a few people, so I have ended up speaking about it a few times. It’s always nice to vary it a little bit from one place to another.

I’d like to start with the Antarctic projects you’ve done, the Halley projects specifically. When you’re working in London in a familiar or normative landscape and then practice in a remote landscape, I wonder has the role of the landscape changed in your work after going somewhere extreme and then coming back or was there an eye-opening experience to nature or landscape you maybe hadn’t seen before?

That’s a very interesting question, I guess—not one I’ve necessarily considered before. I think I’ve always had one particular fascination though, and that is the sky. I’ve always been really interested with the notion of sky, actually particularly in a city where you can be surrounded by very dense construction and looking up to see the sky is that one place where you at once feel in harmony with nature. And I think when we’re working in the Antarctic, because it so featureless the sky assumes an incredibly powerful presence. So when we were working there, we were very keen to introduce light into the building and show that sky off to people. Probably since then, we’ve exploited that all the more through holes in roofs looking up at buildings, drawing light in through the top of buildings, and so on. So I guess it has influenced me in sometimes very subtle and quite abstract ways.

Also from those works you talked about certain systems that you ran into that you hadn’t before: prefabrication and modular systems, insulating systems, and construction methods you hadn’t used before. Do those ideas and concepts carry over into your everyday work at the office?

I think to a degree. You come across things when you’re working on an Antarctic project. And actually a lot of people came to see us and introduced us to technologies that we had never come across before. And so now when you approach another project, every now and then a problem presents itself and it seems almost insurmountable, but then you remember, “Hey, yeah; that’s how we did it when we were working on one of those polar projects, and so maybe we could apply that same logic to this particular problem,” and you come up with a solution to crack an otherwise insurmountable issue. It’s not regular, but it happens now and then for sure.

Some of the other projects you showed were contemporary intervention projects, some of them in historically charged sites. Talk a little bit about how your team develops a concept for what stays and what goes, what you keep, or what becomes new?

Sometimes we work with historic buildings with excessive reverence, and we have to understand that buildings change significantly over time. Sometimes the clarity with which the original designer started off with in working on a project has been diluted by generations that have followed, and has made relatively mediocre additions to make things work purely for them over relatively short periods of time. I think one of the more important things is to try to understand the historical development of the building and see what have been the most crucial moves, and then strip back those layers. It’s a little bit like when you paint over a piece of joinery, over and over again, and you lose all the features. You want to strip it back down to release, at last, the original form of something. That’s really how we approach our buildings. I think the key word is simplification. It’s revealing at last what that building was originally intended for and that helps you when you’re adding to it. It allows you to be quite bold, it allows you to be expressive of your own age, and maybe you adopt a light touch at those points of connection. But otherwise I think you could make quite a clear statement: “Hey, this is who we are, and we are the 21st century, and we’re introducing a whole new life to this building.”

The city of Dallas is in an interesting point on the rise from the economic crisis of the last decade and it is now growing at an exhausting rate. What can you take away from a city like Dallas—back to London and your practice—and either influence or stay away from something? Are there thoughts like this as you walk around?

That’s such a fascinating question because it’s like two issues we combined into one. You visit a city like Dallas and you can see the divisive effect of the road, the way the highway can carve a city up, but also you can see the phenomenally creative ways in which people are now dealing with that issue and connecting the city back together again. Both divisive and connective, the highway is the thing that we learn a lot from when visiting a place like Dallas. Also, of course, there are some truly inspirational projects in the arts here and I’ve really enjoyed visiting, obviously, Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum, coming here to the Nasher Sculpture Center, and seeing the Ando Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth. With each of those projects you learn that the very best architecture, again, evolves out of a respect for simplicity and an understanding of those key features of the human condition: volume, light, and how they interact with the scale of a human being. I’ve really enjoyed seeing projects by masters and I’ll take a lot away from those, that’s for sure.

More news

News 30 November 2020

A new era of Australian Antarctic endeavour

The Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) has appointed Hugh Broughton Architects to join a team led by multi-disciplinary consultants WSP to masterplan the modernisation of the infrastructure at Davis research station in East Antarctica. Initial masterplanning is now complete, and masterplan concept development is ongoing.

News 26 October 2020

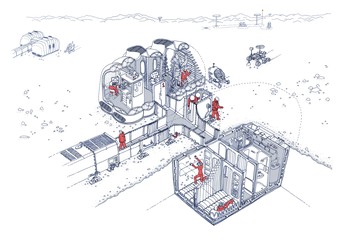

Building a Martian House

A full-scale house designed for future life on Mars has received planning permission in Bristol. The house is the outcome of an ongoing public art project, ‘Building a Martian House’.