Hugh Broughton profile

Published in Architects Choice, 10 November 2018

Hugh Broughton is founder and director of Hugh Broughton Architects. Editor, Jade Tilley, talks to Hugh about modernist influences and the logistics of working in remote locations.

Trained at the university of Edinburgh, Hugh set up his practice in 1995. The team is made up of a core of experienced architects who have worked together for many years. Unusually for a small practice, it has a proven track record in two distinct sectors: heritage projects and buildings for extreme and remote environments. Always pushing boundaries, Hugh and his team are considered leaders in designing for the polar regions. Having worked on remote projects such as Halley VI Antarctic research station, Juan Carlos 1 Spanish Antarctic base, and a new health facility on Tristan da Cunha, their latest competition win led to them joining a team to redevelop Scott base, New Zealand’s only Antarctic research station.

Hugh Broughton

Hugh took some time to talk to Jade Tilley about the firm’s work in remote locations, why it is important to not be pigeonholed, and the architectural influences that have impacted his career.

What is your earliest memory of design and architecture having an impact on you?

When I was very young I enjoyed drawing and I remember my mother saying to me “oh, a good job for you would be an architect – they draw a lot.” Having no idea what an architect was at the age of eight, I read a book about being an architect and it all started from there. I remember visiting an architect who designed fire stations and schools and worked for Surrey County Council. My passion was connected to how buildings worked and understanding their nature.

Where did you study?

I studied at the university of Edinburgh. My professor, Isi Metzstein, ran a practice in Glasgow, Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, and was renowned for designing some of the Cambridge colleges, as well as St Peter's seminary near Cardross, Argyll and Bute. He was a hugely influential professional in my life, along with Andy Macmillan, his lifelong friend and colleague, and head of the Glasgow School of Art. Their work and subsequently their influence on me has been phenomenal.

How do you feel the architectural education system has changed in recent years?

I had thought that it had become too conceptual, which was unfair on the students because they need to be equipped with practical knowledge if they are going to make it in the industry, but my view has changed. Our young students and graduates coming into the practice are very practical and technical; they can do it all.

That aspect of education as philosophical learning has changed, they are now multi-talented and it has completely changed our practice.

What kind of architect did you aspire to be?

I guess I knew I wanted to be embedded in modernist architecture and design. My design approach may have evolved from this, but it certainly provided the foundation. I wanted to design buildings that worked, that were clever and usable.

From an early age I knew I wanted to set up my own office, and now I run said office with all those modernist influences from early on, supported by contemporary ideas. We’re evolutionary; people’s approach to architecture should be, otherwise it will eventually go awry.

I am still highly principled, but with time and acquired skill I’ve become better at compromise and change. Running your own practice you soon discover this, that compromise does not mean abandoning your beliefs, but opening up to considering other solutions. That’s how you evolve.

Who are your architecture inspirations?

My professor, Isi Metzstein, is my first and foremost inspiration.

In my year out I worked for Michael Manser; he was a fantastic person to work for. He gave so much time to us and that is invaluable. My first job after university was with John Mcaslan and Jamie Troughton, who were both very influential on my work. John is incredibly charismatic and a brilliant presenter of his work.

Beyond this, I’m sure you are asking about the influence of the grand masters of architecture whose inspiration goes without saying – but I learned about them through the teachings of Isi, Michael, John and Jamie, and they taught me to apply their influence even when working with the most challenging of clients. They instilled courage and conviction in me.

What does Hugh Broughton Architects represent as an architecture firm?

Most people think of us as the firm that designs in Antarctica, and at first I didn’t mind, but then I became quite anxious of the label and being pigeonholed. Since then, we moved on to create more historically sensitive buildings, giving us a ‘new identity’, but one which we share with many other practices. More recently, in the last two to three years, we have returned to Antarctica and other remote locations. All of a sudden there is more work, and our work on historically sensitive projects combined with our knowledge of remote locations, has served us very well. We have of course pitched for jobs alongside other firms, but our experience in this field has proved to be a huge benefit, so I no longer worry about the label attached to us. I always get excited about the remote locations work, particularly in the case of the Scott Base project: we are facilitating the development and research of these brilliant scientific minds to better understand our planet. It’s no small feat.

Aerial view of the existing Scott Base

How do you continue to carve your own path in the industry as a studio and as an individual?

You must promote what you’re doing. We as a firm continue to carve out that role as a studio that works in remote locations, but we are also conscious of not creating a ‘one size fits all’ approach. We tackle every project as brand new, every situation has unique and specific challenges.

Questioning the brief, based on our experiences, leads us to answers that are unique to each project. I hope that we always approach each new project in this way. If I ever found myself churning out the same solution twice, I’d need to kick myself into touch. What’s interesting about the way that we create and innovate, is that we often come up with the most dynamic solutions in the most mundane of environments – at the kitchen table or travelling on a train.

In the early stages of design it can be easy to get caught up in the motion of the project, but it’s important to ask those different and challenging questions, so you approach it differently and unlock the problems with renewed perspective. The decisions we make on day one have a massive impact; ideas come from all sorts of places and we are always open to exploring them and unlocking new elements.

The Portland Collection

Where is the majority of your work based?

At the moment our portfolio is divided equally between projects in the UK and work in remote locations, but the ratio of projects on remote sites will increase by next year. The closest island is St Kilda, an archipelago off the coast of Scotland.

We have also just completed a healthcare centre in the South Atlantic on Tristan da Cunha, the world’s most remote inhabited island. Then there is the Scott Base redevelopment, New Zealand’s only Antarctic station, on Ross Island. These projects all tend to be pre-fabricated designs, which logistically helps; then at the point where we’re needed on site, we have a highly skilled construction team in place to realise the project. It’s such a shame not being with the team all the time because I enjoy the face-to-face working style. On Scott Base we are working up the design via video conference with our New Zealand partner Jasmax, and have visited all partners regularly to foster a wonderful team spirit, so I know it’s in the best hands. It’s quite an intense working style, so when we do get out there, we’re on a tight schedule and it’s all eyes on the projects and a real singular focus on the work.

10 – 15 years ago people would have been hesitant to employ services from across the other side of the world; technology has accelerated globalisation, so we can now design from a distance and it will only continue to get easier.

What has been your biggest design commission to date?

Definitely Halley VI British Antarctic research station. It’s our biggest project, the most challenging thus far, and the most unique. It transformed our practice entirely. Even our heritage projects have been solidified by our work on Halley VI.

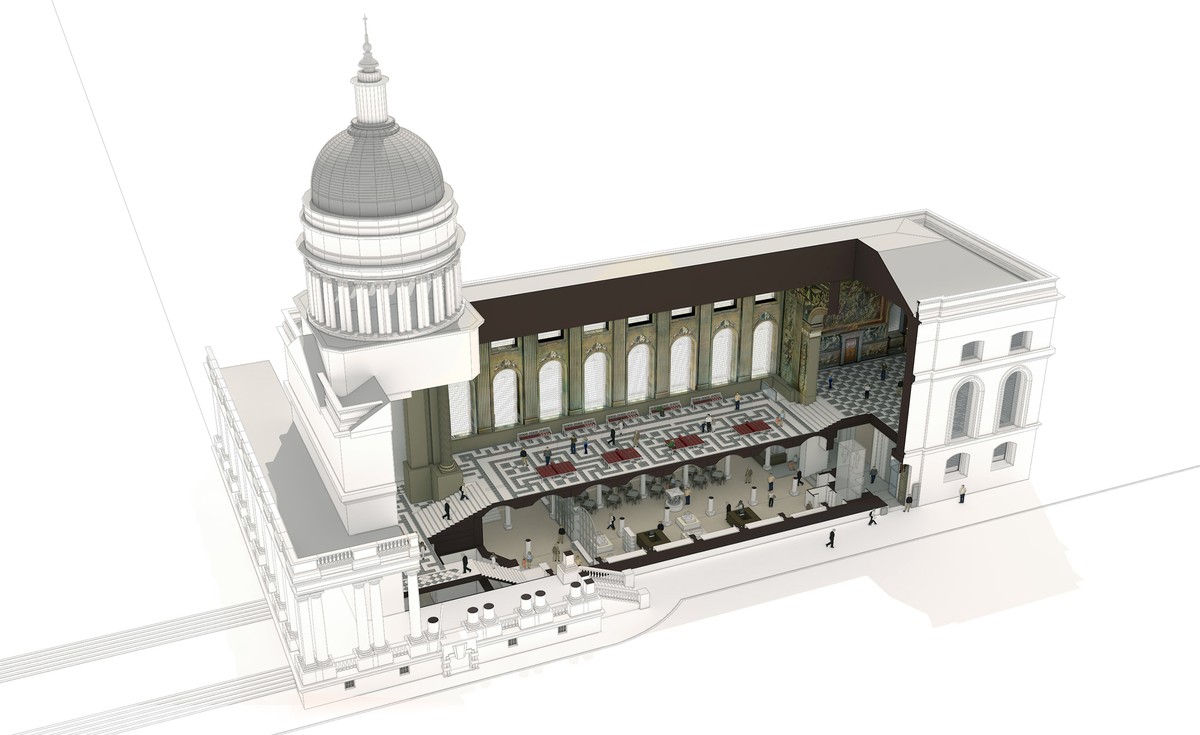

We’re also working on the conservation of a hall in Greenwich, the Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College. It is an Ancient Scheduled Monument and requires a focused attention to detail. With projects like this, you do not leave anything un-investigated in your work to restore and preserve an architecture which is cherished.

What does the face of architecture look like to you in 10 years time?

I think the practice of architecture may become increasingly specialised with technological advances. I don’t mind that, but I do think it’s important not to put all your eggs in one basket, so to speak. We’ll be using technology in ever-more sophisticated ways and it will be more integrated with other members of the wider design team. Age-old skills will hopefully remain relevant though. I see these sorts of changes in our office now; our younger team members are so competent with tech and how to manipulate it, whereas our older team members may find it more challenging. We are conscious of continuing to be responsive and relevant. We take a lead from powerhouses such as Sir Norman Foster; he so brilliantly embraces the new, combining technology and innovation in all his works.

If you hadn’t become an architect what would you be doing?

Well, before I started training as an architect, I worked on a fruit farm, driving a tractor…

Cut-away view of the project for The Painted Hall in Greenwich